Happy New Year SAGT Members!

And welcome to our first “Special Edition Newsletter 2021”.

As our members can probably appreciate, our annual programme is set in the previous year. As we were still under the influence of “Covid-19”, the committee members felt a written format may be appropriate in lieu of our lectures for the first quarter of 2021. This has enabled us to proceed with or without Covid-19 restrictions. So, to start the year off this month, we welcome contributions from a few members, Sandra Spalding, David Smith, and Tami Boden-Ellis and guests with a loose “Scottish” thread. The arts may be celebrated & expressed in many ways and what better way than in music, dance, sculpture, & painting and here you will find a little bit of them all.

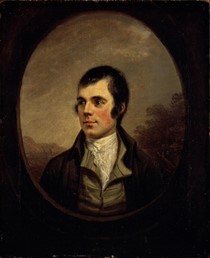

As we are in January and “Scotland” is our theme, we could not not have a bit or two about Robert Burns. From Liz Louis, Curator from the Scotland Galleries we understand; ‘There are surprisingly few contemporary portraits of Robert Burns (1759–1796) who is said to have been a rather reluctant sitter. This small picture by Alexander Nasmyth – on permanent display at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery – is now the best-known portrait of Scotland’s national bard.

Reproduced in almost every conceivable form from postage stamps to shortbread tins, it is now familiar across the world. Here we look at the poet, his portrait, and its painter. While Burns considered emigration, he wrote several of his finest poems: The Twa Dogs, The Cotter’s Saturday Night and To a Mouse all date from 1785. He hoped that by publishing his work, in the now famous Kilmarnock Edition of his poems (1786), he would raise the money to establish himself in Jamaica. But such was the success of the edition that he decided to remain in Scotland, and he was lionised by Edinburgh society.

It was while Burns was in Edinburgh that Nasmyth painted this portrait. Introduced to each other by their mutual acquaintance and patron Patrick Miller of Dalswinton, Burns and Nasmyth became good friends. The portrait was commissioned by the publisher William Creech to be engraved for a new edition of Burns’s poems. As Burns noted:

‘I am getting my phiz done by an eminent engraver, and, if it can be ready in time, I will appear in my book, looking like all other fools to my title page.’

By tradition, Nasmyth’s portrait was painted quickly and left unfinished as the artist was afraid of losing the likeness. While there are few hints of the complexities of Burns’s character, he is depicted as a lively and intelligent young man, set against a landscape background that evokes his Ayrshire roots. Walter Scott, who as a sixteen-year-old had met Burns briefly at an Edinburgh social gathering, later claimed that Nasmyth’s portrait had ‘diminished’ the poet’s features. According to Scott, Burns was ‘strong and robust’ with a certain ‘dignified plainness and simplicity’.

Nasmyth’s image is indeed a rather summary portrayal of Scotland’s most famous son, but this modest work has helped to shape our modern perception of Burns and the qualities of democracy, generosity and honesty that we now associate with his personality and his writing.

Robert Burns was born at Alloway in Ayrshire, the son of a farmer who provided him with an excellent education. On the death of his father in 1784, Burns tried his hand at farming, but met with little success.

Burns and Nasmyth became firm friends, sharing a love of nature as well as an interest in radical politics. On his trips to Edinburgh, Burns was a frequent visitor to Nasmyth’s studio, and they often walked together in the surrounding countryside. In 1828, many years after Burns’s early death, Nasmyth made another portrait of him, this time showing the poet standing against a view of the Auld Brig o’ Doon at Alloway in his native Ayrshire. This more Romantic image is also in the collection of the Portrait Gallery.

Next is the Painting, “Minister on the Loch” by Henry Raeburn (1756-1823)

The Skater is thought to be the Reverend Robert Walker, minister of the Canongate Kirk and a member of the Edinburgh Skating Society, skating on Duddingston Loch on the outskirts of Edinburgh 1795. The painting is in the National Gallery of Scotland, well worth a visit.

We learn that there is a Scottish Country Dance called ‘Minister on the Loch’ a Strathspey (3 x 32) for three couples, i.e., 32 bar strathspey danced three times through. Composed by Roy Goldring, this is an extremely popular dance and appears on dance programmes regularly. A demonstration of the dance can be viewed on U-Tube.

Last but not least is the annual celebration of the Scottish Poet Robert Burns, born 25th January 1759 and died 21st July 1796. Burns Night suppers are held in many parts of the world on the 25th of January. The menu consists of Cock-a-leekie soup, Haggis,neeps and tatties, Cranachan or Scottish triffle. The Supper begins with the Selkirk Grace and ‘attreebute tae Robert Burns’: Some hae meat and canna eat, and some wad eat that want it, But we hae meat and we can eat, Sae let the Lord be thankit. The Haggis is paraded in behind a Piper and the Address to a Haggis follows. The first verse: Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face, Great Chieftain o’ the puddin’-race! Aboon them a’ ye tak your place, Painch, tripe, or thairm: Weel are ye wordy o’ a grace As lang’s my arm.

Burns also composed love poems which were set to music, such as Ae Fond Kiss and My Luve is like a Red, Red Rose. The song that is sung, most often after Ceilidhs, dances, parties, and Hogmanay is, of course, Auld Lang Syne

And the triple link between The Minister on the Loch dance, Scottish dancing in general and Burns is this: In his 17th year, Robert Burns attended a Scottish dance school. The teacher was William Gregg, who was born in 1766 in Ayr. William would have accompanied the lessons on his fiddle and that same fiddle is to this day on display at the Burns Birthplace Museum in Alloway. (SS) Duke of Wellington statue, Glasgow.

When you think of Glasgow’s rich cultural heritage you think of many things: The School of Art building; the Mackintosh tearoom; the Burrell Collection in Pollock Park; the Gallery of Modern Art; the Kelvingrove Art Gallery. But it is perhaps what is outside the Gallery of Modern Art which should attract your attention. For here, on his plinth, is a statue of the Duke of Wellington on his horse. And it is this statue which, according to Wikipedia, is “one of Glasgow’s most iconic landmarks” and which Culture Trip says is “testament to the priceless Glaswegian and Scottish sense of humour”.

Designed by the Italian sculptor Carlo Marochetti and erected in 1844, for his first 140 years the Duke attracted no particular attention. Then one night in the 1980s the Duke acquired a hat – or to be more precise, a traffic cone. It is thought, though there are many theories, that it might have been a student – rather fou after a night on the bevvy – who put it there. The authorities removed the cone, it appeared again. The authorities removed it, it reappeared. This went on, at an alleged cost of £10,000 per year to remove the cones, until the City Council decided to put a stop to it by doubling the height of the plinth. A petition was raised to save the statue as it was, and this acquired 10,000 signatures in 24 hours. The Council backed down.

It was perhaps inevitable that, when Glasgow hosted the Commonwealth Games in 2014, the statue with cone should make an appearance at the opening ceremony. And, when the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society held its annual Spring Fling for younger dancers in Glasgow in 2018, what else could possibly be the logo for that?

So when you next head to Glasgow, do take in all the wonderful cultural heritage – but also, do walk to the Gallery of Modern Art on Royal Exchange Square, just south of Queen Street Station, and say “hello” to the Duke. Ye cannae miss him – he’s the wan with the cone on his heid!! (DS)

Our concluding contribution is a bit on Joan Eardley (1921 – 1963). We understand from Becky Manson, Curator: The last century had seen some artists in Scotland exploring the theme of identity and one artist was Joan Eardley. Eardley painted both portraits of children in deprived suburban Glasgow and depictions of dramatic landscapes which chart the changes of season celebrate two distinct aspects of Scottish identity: the urban and the rural. Despite her untimely death at the age of 42, Eardley remains one of Scotland’s best loved artists.

Eardley was born in Sussex in 1921 but moved to Scotland with her family in 1939 – taking up residence in Bearsden, a suburb to the northwest of Glasgow. Eardley enrolled at Glasgow School of Art in 1940, graduating in 1943 with a diploma in Drawing and Painting. In the early 1950s, the artist rented a studio in the Townhead area of Glasgow. It was here that Eardley’s interest in documenting the children who played in the back streets of the city began.

In the early 1960s Eardley said: ‘some [children] interest me much more as characters… these ones I encourage – they do not need much encouragement – they do not pose – they come up and say, “will you paint me?” There are always knocks at the door… I try to get them to stand still – it is not possible to get a child to stay still… I watch them moving about and do the best I can’.

Alongside the children of Glasgow, Eardley’s other major inspiration was arguably a small village in Aberdeenshire. She seems to have had a special relationship with Catterline – a coastal village on the North Sea, that the artist first visited in 1951. During a period of illness, Eardley discovered Catterline on a drive with her friend, Anette Soper. That same year, Soper bought a small building on a cliff top, from which she and Eardley could paint. In 1955 Eardley purchased her own cottage there – travelling back and forth between the village and her home in Glasgow until her death in 1963. It is suggested that the seascapes she created during this time are some of the artist’s most personal images, with Eardley herself stating that the more she got to know a particular place, the more she found to paint there. Though Eardley’s final works focused again on urban Glasgow’s children, the artist’s affinity with the rural village’s stormy seas are evident. Following her death, Eardley’s ashes were scattered on the beach at Catterline.

No comment yet, add your voice below!